Billboard ads, socks, plates, even kickboxing: are these really matters of artistic freedom? The boundary is more blurred than it seems. What is clear is that threats to creative expression rarely arrive in clean, visible lines. They move quietly. Under-reported incidents. Weak reporting systems. People in the field know the limits of numbers. They track trends, set baselines, but rarely capture the texture of constraint.

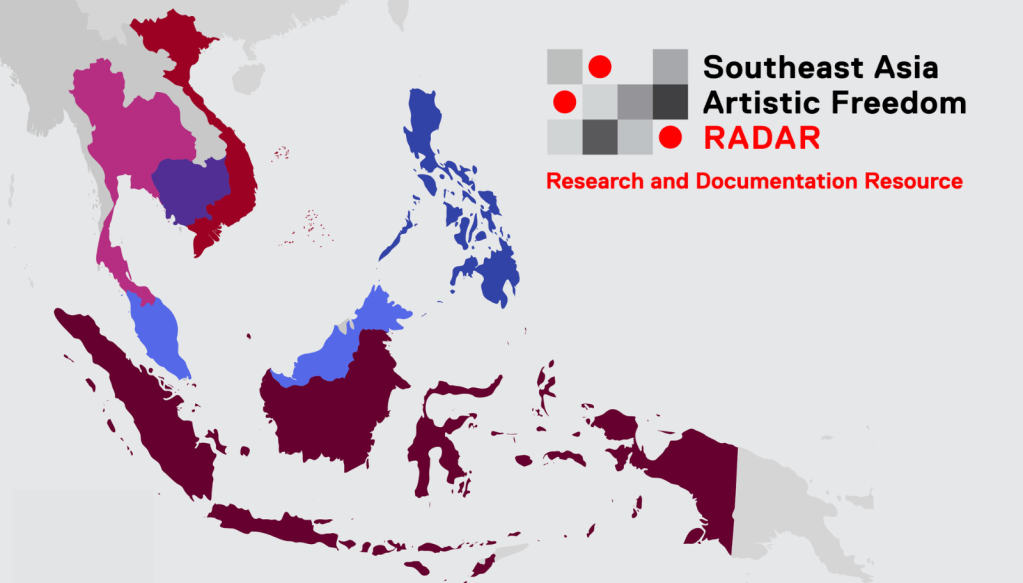

When ArtsEquator, a Singapore-based organisation focused on Southeast Asian arts practice, quietly launched RADAR (Research and Documentation Resource), in September, the release reflected the breadth of its rights-based approach. Portrayed as the first searchable archive of its kind, RADAR gathers the violations, bans, and hidden constraints that shape creative life across six countries: Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, and the Philippines. The database contains more than eight hundred cases dating back to 2010.

For ArtsEquator’s co-founder and head researcher Kathy Rowland, and to data-tool specialist Kai Brennert, the system is not simply a monitoring device or a repository of censored cases. They describe it as an attempt to counter a deeper and more insidious threat: the slow, everyday erosion of cultural memory.

‘We see RADAR primarily as a research tool’, Kathy says. ‘Documentation, information, and history matter. Remembering is a form of accountability’. Her background, straddling arts management, literary writing, and cultural organising, shaped the project’s architecture. Kai brings a data-driven perspective to the question of artistic freedom. Rather than building an activist-heavy advocacy platform, RADAR works quietly: gathering granular, verified data; collaborating with country researchers; and mapping patterns that are often invisible to the public. ‘We do small things’, she adds. ‘We don’t take on huge tasks. For us, resisting erasure is already a political act’.

Artistic Freedom Is Not an East–West Divide

Asked whether Southeast Asia has its own culturally specific notion of artistic freedom, distinct from Western liberal models, Kathy pushes back. ‘Freedom is freedom’, she says. ‘People everywhere want the same ability to express themselves’. What differs are the social and political contexts shaping that expression. Even in the United States, she notes, cultural institutions are now cautiously negotiating what they can publicly say. ‘It’s not an east–west issue. It’s contextual. Societies move through different phases’.

RADAR’s database includes cases that fall far outside traditional notions of ‘the arts’: advertising disputes, food controversies, even nationalistic debates over regional kickboxing traditions. To the RADAR team, these are not outliers. They are essential. ‘When we look at arts, culture, and creativity, we are really looking at civic space’, Kathy explains. ‘What we have observed is that there is a kind of control applied to all forms of expression, including creative expression’.

She cites Southeast Asian debates over food, dishes tied to specific ethnic communities becoming cultural flashpoints when adapted by another group. ‘Culture is a whole practice of life’, she says, drawing on cultural critic and theorist Raymond Williams. ‘Popular culture, heritage, identity… They all intersect’.

Kai gives a striking example: rival claims over traditional Southeast Asian kickboxing practices, which predate modern geographical borders. What begins as heritage pride hardens into national essentialism, then into political conflict. ‘It becomes weaponised’, he says. ‘And that’s why it belongs in our data’. The point connects, he adds, to how artistic freedom itself is defined. ‘It also tells you something about your earlier question, about whether artistic freedom might be perceived differently in Southeast Asia. Perhaps it relates to what culture is, or what we consider part of the cultural realm’.

Documenting What Stays Hidden

One of RADAR’s most difficult challenges is capturing what Kathy calls ‘under the radar’: acts of censorship deliberately designed to leave no trace. A police officer instructing an artist in Vietnam to quietly remove a work without documenting the order. A venue abruptly withdrawing permission. A permit delayed indefinitely, with bureaucratic excuses standing in for ideological objections. Nothing is said explicitly. Nothing is written down. ‘Everyone recognises these tactics’, Kathy says. ‘But how do you verify something that leaves no evidence?’ The result is a landscape where artists navigate uncertainty and suspicion, and researchers struggle to record events that power structures prefer to leave in the dark.

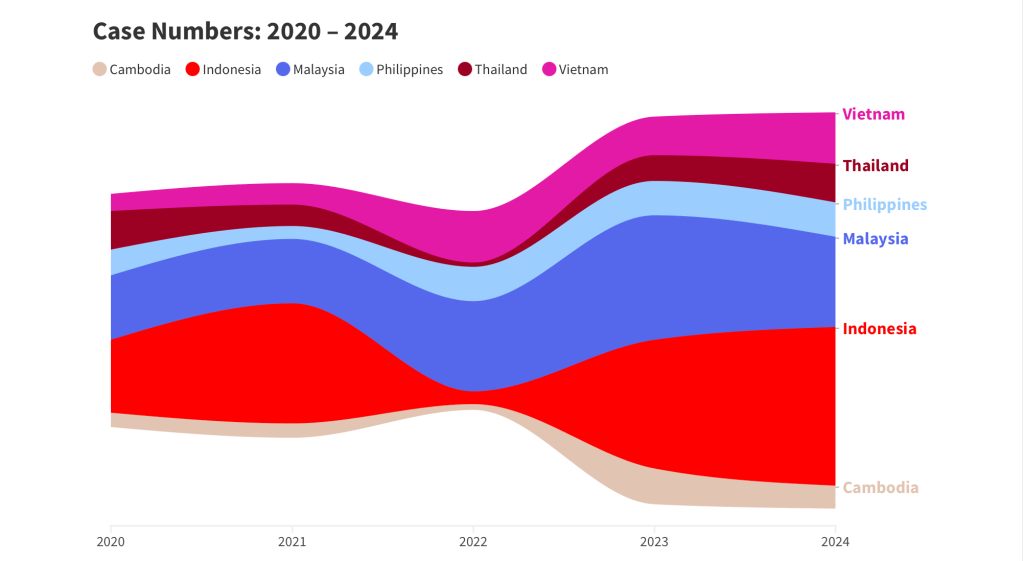

Each case in RADAR’s database contains more than fifty data points, sometimes closer to seventy. When the ArtsEquator team set out to simplify the system, originally created under a pilot program in 2022, they somehow ended up with even more. In Germany, as Kai explains, there is a word for this: ‘Verschlimmbesserung’, the act of making something worse by trying to make it better. The density, he says, is intentional. ‘We want nuance. Numbers alone won’t show how artistic freedom is being challenged’. The team collects categorical data, who the actors are, when interventions occur, what themes are involved, but also narrative summaries. ‘We’re not just capturing numbers. We’re capturing stories’. Country researchers play a key role here, supplying the context that gives the data its shape. ‘Only after a few years, with more and more cases, can you see the trends that emerge’, Kai says. ‘But if your threshold is too high, and you don’t capture those early signals, you lose the ability to track how those trends develop’.

Gender is one example of this layered approach. RADAR tracks: the gender of the creator; whether the work deals with gender issues; whether gender-based tactics were used against it, and whether officials justified restrictions on gendered grounds. ‘It matters’, Kathy says. ‘We want very deep data points because we want to be able to track patterns. Ten years ago, was this an issue? Is it less of an issue now? What is changing? What is emerging?’ They also distinguish between pre-production and post-production censorship, a key indicator of whether states are relying on pre-emptive suppression or punitive, after-the-fact punishment.

Beyond the Database: Tracking What Happens Next

RADAR’s website is visually striking, but the question is what happens once ArtsEquator turns that data into visualisations. What patterns begin to appear? The team works through a multistep process. Once cases are verified and uploaded, usually months after collection, ArtsEquator conducts cross-tabulations, looking for meaningful patterns. Hints often come from the researchers on the ground, who notice shifts before the numbers reflect them.

One of the clearest trends so far is that while most censorship begins with the state, the public is emerging as a powerful force. ‘The first step is often public outcry’, Kai says, sometimes organic, sometimes fuelled by government-affiliated or religious groups. Only after this public reaction do authorities intervene, and sometimes the prosecution follows. This multi-stage pathway (public protest, police action and legal consequences) is now one of RADAR’s most striking visualisations. ‘There are multiple actors involved’, Kai explains. ‘It doesn’t fit neatly into a single category’.

In the realm of artistic freedom, tracking what happens next, when shows are reinstated, charges dropped, or policies revised, and folding that information back into advocacy can be a difficult task. Kathy acknowledges that this is a persistent challenge across the field. Updating cases is an ongoing task. As artists come forward with older incidents, inspired by RADAR’s existence, past datasets must be revised. ‘We note clearly that the database reflects only what we know at a given moment’, Kathy says. ‘It doesn’t capture everything’. But RADAR produces much more: country reports, videos, essays, policy mappings, and contextual analyses.

In places like Cambodia, Kai adds, a new trend is emerging. Not specific incidents, but blanket restrictions through guidelines or announcements. These are often nonbinding yet powerful, operating through fear rather than enforcement. ‘That’s harder to capture in a database’, he admits.

AI, Accuracy, and Ethical Boundaries

Given the complexity of monitoring artistic freedom, the team has also had to consider how large language models (AI systems trained on vast amounts of text to generate human-like language) might fit into the workflow. They also need to determine what safeguards are required to prevent these systems from distorting or sanitising sensitive material. Some case summaries in RADAR are noted as ‘edited using AI’, an approach the team adopted during the early pilot. High-risk inaccuracies required correction, but rewriting 600 summaries was financially impossible. So AI was used sparingly, for basic editing only, and always followed by human review. Crucially, no confidential cases were fed into any model. ‘I’m more suspicious of who owns the technology’, Kathy says. ‘Not of technology itself’. RADAR now relies on researchers’ discretion. Some use AI for translation, but it is not embedded in the formal methodology.

RADAR’s greatest challenge is not logistics or funding, but safeguarding researchers. ‘They’re on the ground’, Kathy says. ‘They take the risks’. Language also adds complexities as most of the countries in the region are multilingual. Geography matters too: Vietnam is relatively straightforward; Indonesia and the Philippines, with their vast archipelagos, are not. But despite the difficulties, RADAR is committed to openness. ‘We are always happy to share our data’, Kathy emphasises. ‘Anyone using it for artistic rights, policy analysis, or supporting artists, we want to work with them’.

RADAR remains a young initiative, still refining policies, rewriting guidelines, and adjusting workflows. And, at times, creating its own ‘Verschlimmbesserung’, as the team jokes. Mistakes happen. Systems evolve. But the aim remains steady: to document cultural repression with rigor, nuance, and humanity. ‘We’re resisting erasure’, Kathy says. ‘And sometimes remembering is the most powerful act of all’. She returned to that thought at the end of our conversation, as if to remind me that memory, too, is a form of resistance.