In Türkiye today, there is deep anxiety. The media is widely distrusted by many, while the political environment grows more oppressive for those who question the government. All of this has been unfolding against the backdrop of a troubled economy – after peaking at 85% in 2022, inflation fell to below 50% by October 2024, but uncertainty remains.1 The overall picture is far from reassuring. Artists in Türkiye can be a powerful source of hope, yet optimism is fading as freedom of artistic expression, as past years have proved, over and over, is under pressure. This was illustrated by the rising number of cancellations and censorship cases across the country in 2024, pointing to a worrying trend for artistic freedom. In May 2025, Türkiye will come before the U.N. Human Rights Council and undergo its fourth Universal Periodic Review (UPR). Seizing this opportunity, Freemuse and SUSMA – Platform 24 made a joint submission that highlights restrictions on freedom of expression, artistic freedom, and cultural expression – in particular, restrictions targeting LGBTQ+ groups and Kurdish artists.2 The report underscores the growing restraints on the arts and civil society. But this won’t surprise those who have been following freedom of expression in Türkiye.

How did we get here? First following the Gezi protests of 2013, and then more sharply after the 2016 coup attempt, the country entered a new struggle for civil liberties and human rights.3 In response, the government imposed a state of emergency and introduced further restrictions – measures that critics argue were used to suppress opposition voices, including artists, journalists, writers, and academics. In a country marked by authoritarian tendencies, political unrest, and economic instability, cultural workers have at times been cast as enemies of the state. What is particularly alarming is that as the political landscape darkens, many artists find themselves growing increasingly uneasy. This unease is further fuelled by the misuse of Laws No. 2911 and 5442 to restrict peaceful gatherings and arts events, as well as the frequent application of Article 216 to suppress artistic freedom – particularly targeting minoritised groups. Similarly, Türkiye’s Anti-Terror Law is widely criticised for its broad use against artists and writers, often charging them with “terrorist propaganda” or militant ties with little evidence.

Kurdish music under siege

Kurdish music, language, and culture have long been marginalised in Türkiye. Throughout 2024, as the joint Freemuse and SUSMA – Platform 24 UPR submission documented, Kurdish artists faced a wave of concert cancellations, both in predominantly Kurdish areas such as Siirt, Diyarbakır, Ağrı, Muş and Erzurum, as well as in Istanbul. Artist Diljen Roni, whose November concert was cancelled citing “renovation”, said “Art is a power that ensures the survival of our culture and language. As artists who strive to keep Kurdish music and language alive, we are determined despite these obstacles. We believe in the unifying power of art, and we are sure that we will meet again with you, our valuable listeners, on a freer platform. In the face of these injustices, we will continue our struggle for a more just future.”4 The cancelation was one of several that took place across Türkiye on spurious grounds.

Such arbitrary prohibitive attitudes, especially by Turkish municipalities, who were responsible for the majority of these decisions, is worrying. When municipalities act as gatekeepers by cancelling concerts or events, it raises serious concerns about institutional censorship and ongoing state efforts to control cultural narratives, particularly those tied to Kurdish identity and language. In Türkiye, Kurdish music and art are often cast as political provocations rather than cultural contributions, their very existence framed as a threat to national unity. The result is not only the suppression of a minority’s voice but a narrowing of the cultural landscape itself, where access to diverse artistic expression is curtailed, and the possibility of dialogue between communities is steadily eroded.

Censorship expands to streaming services

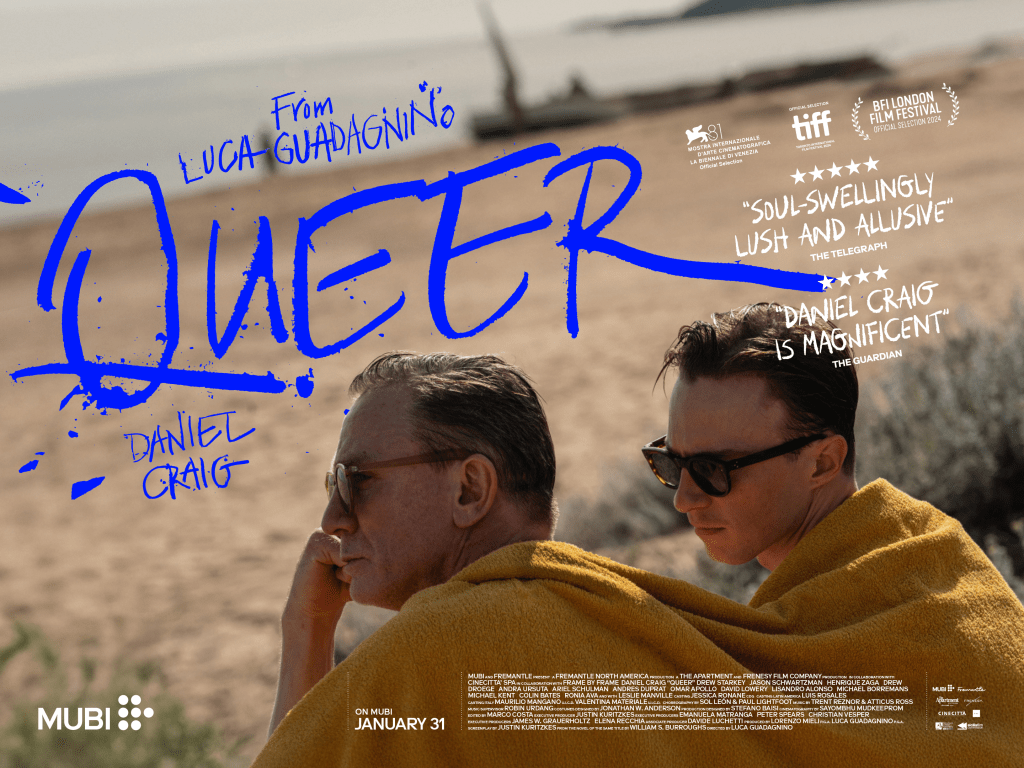

In 2024 the grip of institutional censorship tightened, with the Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTÜK), a state agency, extending its reach to subscription-based platforms such as Netflix, Prime Video, Blu TV, and MUBI. Its recent orders to the platforms instructing them to remove films like Sausage Party: Foodtopia, for its sexual innuendo violating “general morality”, and Doctor Climax, for explicit depictions of violence and sexuality labelled as “immoral content”, are prime examples of institutional censorship.5 RTÜK’s rationale is grounded in protecting “general morality” and “family structure”, citing explicit violence, sexuality, homosexuality, and drug use as problematic content. Similarly, the situation at Mubi Fest Istanbul 2024 underscored the growing restrictions on artistic expression. The Kadıköy District Governorate of Istanbul banned the opening film Queer, an Italian-American co-production, citing its “provocative content” as a threat to “public peace”. The decision prompted the festival’s cancellation by its organiser, Mubi.6 Queer, an adaptation of William Burroughs’s novel about a gay expatriate in Mexico, stars Daniel Craig, the internationally renowned actor. In a statement, Mubi condemned the ban, calling it “a direct restriction on art and freedom of expression.” The statement continued: “Festivals are spaces that celebrate art, cultural diversity, and community, bringing people together. This ban not only targets a single film but undermines the very essence and purpose of the festival.” Both cases, restrictions on the streaming platforms and on the film festival, reveal the role of governmental and institutional actors in regulating art in Türkiye, particularly when it touches on politically sensitive issues such as sexuality, identity, and social norms.

Institutional censorship and the Biennial

Censorship in Türkiye is prevalent, whether imposed by governmental or non-governmental institutions. The Istanbul Foundation for Culture and the Arts (İstanbul Kültür Sanat Vakfı (İKSV)), for instance, ignored an international panel’s recommendation to appoint curator Defne Ayas for the 2024 Istanbul Biennial. An official reason for this has not been disclosed. However, critics link the decision to a controversy involving Ayas in 2015, when she was the curator of the Turkish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. A reference to the “Armenian genocide” in an essay included in the exhibition catalogue had prompted government intervention and resulted in the catalogue’s withdrawal.7

At any rate, instead of appointing Ayas for the 2024 Istanbul Biennial, the İKSV opted to go with Iwona Blazwick, a member of the Biennial’s advisory board, as curator. This sparked debate, with artists criticising İKSV for lacking transparency and ethics. Unsurprisingly, the controversy led to the 18th Istanbul Biennial being postponed to 2025, with a new curator appointed after Blazwick herself resigned. As one of Türkiye’s oldest and most influential cultural institutions, İKSV’s actions are significant. Moreover, they represent a clear conflict between artistic freedom and political pressure.

LGBTQ+ artists and subtle resistance

LGBTQ+ artists and exhibitions touching on this theme face growing challenges. In July, for instance, the Beyoğlu District Governorship banned Dön-Dün-Bak, an exhibition on the trans movement in Türkiye at the Depo gallery, citing “public hatred”. This ban, coming in the wake of anti-LGBTQ+ protests at a separate art show last year, has rattled artists and cultural workers.8 “To be honest, half of our energy is going towards how we can create some safe space—not just for the organisations involved, the artists, and ourselves, but also for the audience,” curator Alper Turan told Hyperallergic. “We’re talking about which neighbourhood will be safe for them to come to. That is new for me.”9

Such incidents have become increasingly common in Türkiye, as documented in the joint UPR submission by Freemuse and SUSMA – Platform 24. But with political pressure mounting, many artists have to navigate a delicate line between creative expression and self-censorship. As overtly touching on LGBTQ+ themes becomes increasingly risky, artists are responding by finding subtle forms of resistance and adapting their work to evade restrictions while still pushing boundaries. One example is the Sınır/Sız (Border/Less) collective, which organises exhibitions featuring underrepresented LGBTQ+ artists. However, they carefully avoid directly associating art events with Pride Month or using overt LGBTQ+ language, often opting for alternative modes of expression instead. For example, the collective will exhibit work by Furkan Öztekin, who uses collage and abstraction to explore themes of belonging and loss. As Öztekin explains, “These political threats and restrictions drive us to find alternative forms of resistance … If colours are banned, we propose black-and-white exhibitions; if forms are restricted, we create shows with amorphous shapes.”10

The intersection of art, politics, and identity in Türkiye reveals a deep struggle for artistic freedom amid increasing censorship and societal pressures. Kurdish and LGBTQ+ artists face significant barriers, while both governmental and non-governmental institutions often suppress diverse cultural expression. The state’s tightening grip on streaming platforms and film festivals further restricts content that challenges political and social norms. This climate of repression, reinforced by anti-terror laws, has led many institutions, artists, and curators to self-censor, fearing government reprisal. What is striking is that self-censorship has become a survival mechanism in an increasingly polarised and politically controlled environment. It can also be “a way to create a feeling of safety in a very insecure environment,” said Ozan Ünlükoç, a member of the Sınır/Sız team.11 But this still creates a chilling effect whereby artistic expression is not just limited by external forces but also by the internalised understanding of what is “safe” to exhibit or curate. Despite these challenges, art remains a powerful force for resistance and unity. As the Freemuse and SUSMA – Platform 24 joint submission highlighted, measures must be taken to protect freedom of artistic expression and inclusivity in Türkiye’s cultural landscape. This includes ensuring that artistic works are not subject to anti-terror legislation and taking action to end non-elected officials’ use of Laws 2911 and 5442 to restrict peaceful gatherings and arts events, particularly targeting minoritised groups.

1 A. Samson, “Turkish inflation falls below 50% in boon to Erdoğan”, Financial Times, 3 October 2024, https://www.ft.com/content/3ca2bf-cb-156d-4f73-bf58-e8ea60f8cbc2, (accessed 10 December 2024).

2 “Joint Stakeholder Submission to the UPR of Türkiye”, Freemuse and Susma – Platform 24, 1 November 2024, https://www.freemuse.org/freemuse-highlights-turkiyes-growing-restrictions-on-arts-and-civil-society, (accessed 1 December 2024).

3 M. Lowen, “Erdogan’s Turkey”, BBC, 13 April 2017, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-sh/Erdogans_Turkey, (accessed 10 December 2024).

4 “Kürtçe konserler arka arkaya iptal ediliyor”, Susma 24, 11 November 2024, https://susma24.com/kurtce-konserler-arka-arkaya-iptal-ediliyor/, (accessed 30 November 2024).

5 “RTÜK’ten Netflix, MUBI ve Blu TV’ye Ceza”, Susma 24, 1 August 2024, https://susma24.com/rtukten-netflix-mubi-ve-blu-tvye-ceza/, (accessed 30 November 2024).

6 A. Ritman, “‘Queer’ Ban in Turkey Prompts Mubi to Cancel Festival in Country”, Variety, 7 November 2024, https://variety.com/2024/film/global/mubi-cancels-turkish-festival-queer-banned-1236203872/, (accessed 30 November 2024).

7 “Four artists withdraw from İstanbul Biennial over curator controversy”, Bianet, 23 October 2023, https://bianet.org/haber/four-artists-withdraw-from-istanbul-biennial-over-curator-controversy-286763, (accessed 30 November 2024).

8 J. Hattam, “Pro-Erdoğan Protesters Target Istanbul Exhibition Deemed LGBT Propaganda”, Hyperallergic, 30 June 2023 https://hyperallergic.com/831172/ pro-erdogan-protesters-target-istanbul-exhibition-deemed-lgbt-propaganda/, (accessed 30 November 2024).

9 J. Hattam, “Turkey’s Queer Art Community Walks a Thin Line”, Hyperallergic, 17 November 2024, https://hyperallergic.com/966639/turkey-queer-art- community-walks-a-thin-line/, (accessed 30 November 2024).

10 J. Hattam, “Turkey’s Queer Art Community Walks a Thin Line”, Hyperallergic, 17 November 2024, https://hyperallergic.com/966639/turkey-queer-art- community-walks-a-thin-line/, (accessed 30 November 2024).

11 J. Hattam, “Turkey’s Queer Art Community Walks a Thin Line”, Hyperallergic, 17 November 2024, https://hyperallergic.com/966639/turkey-queer-art- community-walks-a-thin-line/, (accessed 30 November 2024).

*This article published in Freemuse’s State of Artistic Freedom 2025 report.